by Nick

Posted on 03 December, 2015

Sheri Fink published this nice piece in the New York Times yesterday on the legal issues surrounding state-imposed quarantines on travelers returning from countries with widespread Ebola transmission. In addition to the toll these policies have had on the individuals who have been put under quarantine, I took away from this article that there is still a need for better data on and communication about the risks of travelers being infected with Ebola. As it happens, this is the topic of my talk today at the Epidemics5 conference.

The CDC recommends active monitoring of individuals at high-, some-, and low-risk of Ebola infection. They encourage that state and local public health authorities to monitor individuals for symptoms of Ebola until 21 days after the individual’s last possible exposure. Thousands of individuals have undergone active monitoring over the last year.

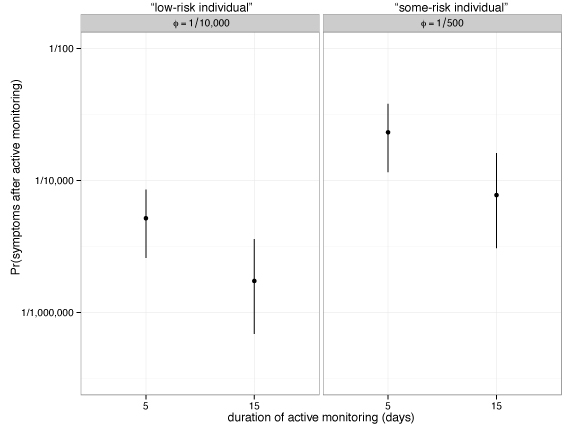

Using a few simple assumptions about the baseline risk of developing symptoms and the duration of time between exposure to Ebola and the beginning of monitoring, we have estimated the probability that an individual develops symptoms after an active monitoring period ends. Our calculations (see figure above) suggest that having a single duration or frequency of monitoring may result in quite different probabilities for individuals from different exposure categories. For example, under our assumptions, monitoring an individual with a 1 in 10,000 chance of developing symptomatic illness for 5 days gives rise to between a 1 in 10,000 and 1 in 100,000 chance of developing symptoms. Similarly, monitoring a higher-risk individual who has a 1 in 500 chance of developing symptomatic illness for a longer duration of 15 days yields a roughly similar chance of developing symptoms.

Our hope is that this work (which is still very much in progress) offers up some simple ways of looking at these data and risks that can communicate both what we know and don’t know about a set of low-probability and high-cost scenarios in a way that is digestible to the general public and to public health decision-makers.

Here is the full slide deck for this talk: